Equity Options

What is the tax treatment of premiums received from the sale of put and call options?

Option holders

If you hold options, they will either:

(1) expire un-exercised on the expiration date because they are worthless,

(2) be exercised because they are “in the money” or

(3) be sold before they expire.

If your option expires, you have obviously sustained a capital loss — usually short term because you held the option for one year or less. But if it was held longer, you have a long-term capital loss. For example, say you buy a six-month put option with a strike price of $10 per share. On the expiration date the stock is selling for $20. If you have any sense, you’ll let the option expire and thereby incur a short-term capital loss. Report the loss — which is the price (or premium) you paid for the put, plus transaction costs — on Part I of Form 8949, which feeds into Schedule D, by entering the option-purchase date in column (c), the expiration date in column (d), “expired” in column (e), and the cost, including transaction fees, in column (f).

If you exercise a put option by selling stock to the writer at the designated price, deduct the option cost (the premium plus any transaction costs) from the proceeds of your sale. Your capital gain or loss is long term or short term depending on how long you owned the underlying stock. Enter the gain or loss on Form 8949, just as you would for any stock sale.

If you exercise a call option by buying stock from the writer at the designated price, add the option cost to the price paid for the shares. This becomes your tax basis. When you sell, you will have a short-term or long-term capital gain or loss depending on how long you hold the stock. That means that your holding period is reset when you exercise the option.

For example, say you spend $1,000 on a July 8, 2014, call option to buy 300 shares of XYZ Corp. at $15 per share. On July 1 of 2015, it’s selling for a robust $35, so you exercise. Add the $1,000 option cost to the $4,500 spent on the shares (300 times $15). Your basis in the stock is $5,500, and your holding period begins on July 2, 2015, the day after you acquire the shares.

If you sell your option, things are simple. You have a capital gain or loss that is either short term or long term, depending on your holding period.

Option writers

As mentioned, option writers receive premiums for their efforts. The receipt of the premium has no tax consequences for you, the option writer, until the option:

(1) expires un-exercised,

(2) is exercised or

(3) is offset in a “closing transaction” (explained below).

When a put or call option expires, you treat the premium payment as a short-term capital gain realized on the expiration date. This is true even if the duration of the option exceeds 12 months. For example, say you wrote a put option at $25 per share for 1,000 shares of XYZ Corp. for a $1,500 premium. This creates an obligation for you to buy 1,000 shares at a strike price of $25. Fortunately for you, the stock soars to $35, and the holder wisely allows the option to expire. You treat the premium from writing the now-expired option as a $1,500 short-term capital gain. Report it on Part I of Form 8949 as follows: Enter the option expiration date in column (c), the $1,500 as sales proceeds in column (e), “expired” in column (f). If you wrote the option in the year before it expires, there are no tax consequences in the earlier year.

If you write a put option that gets exercised (meaning you have to buy the stock), reduce the tax basis of the shares you acquire by the premium you received. Again, your holding period starts the day after you acquire the shares.

If you write a call option that gets exercised (meaning you sell the stock), add the premium to the sales proceeds. Your gain or loss is short term or long term, depending on how long you held the shares.

With a closing transaction, your economic obligation under the option you wrote is offset by purchasing an equivalent option. For example, say you write a put option for 1,000 shares of XYZ Corp. at $50 per share with an expiration date of July 5, 2015. While this obligates you to buy 1,000 shares at $50, it can be offset by purchasing a put option for 1,000 shares at $50 per share. You now have both an obligation to buy (under the put option you wrote) and an offsetting right to sell (under the put option you bought). For tax purposes, the purchase of the offsetting option is a closing transaction because it effectively cancels the option you wrote. Your capital gain or loss is short term by definition. The amount is the difference between the premium you received for writing the option and the premium you paid to enter into the closing transaction. Report the gain or loss in the tax year you make the closing transaction.

Straddles

For purposes of deducting losses from options, the preceding rules apply to so-called naked options. If you have an “offsetting position” with respect to the option, you have a “straddle.” An example of a straddle is when you buy a put option on appreciated stock you already own but are precluded from selling currently under SEC rules. Say the put option expires near the end of the year. If you still own the offsetting position (the stock) at year’s end, your loss from the expired option is generally deductible only to the extent it exceeds the unrealized gain on the stock. Any excess loss is deferred until the year you sell the stock.

Can you offset the gain from the sale of options with capital losses realized from the sale of stocks?

Is the gain or loss from the sale of LEAPs treated as long-term or short-term?

What is a qualified covered call?

A call constitutes a qualified covered call only if it meets at least three basic conditions.

First, the call's strike price must not be too deep in-the-money, which means that the strike price must be close to the closing price for the stock on the previous day. The minimum strike price required for QCC status is usually one strike below the stock's previous day's closing price. In addition, the strike price must be at least 85% of the closing price.

Second, options on the underlying stock must be listed on an options exchange. The call in question does not need to be listed, but some option on the underlying stock must be listed.

Third, when the investor enters into the call, it must have more than 30 days remaining to expiration but not more than 33 months.

What is a deep-in-the-money option?

Deep in the money is an option with an exercise price, or strike price, significantly below (for a call option) or above (for a put option) the market price of the underlying asset. Significantly, below/above is considered one strike price below/above the market price of the underlying asset.

How are index options taxed?

According to Section 1256 of the Internal Revenue Code, certain financial contracts - called "Section 1256 contracts" - are treated differently than other products when the holding period is less than one year. These contracts include:

Regulated futures

Foreign currency contracts

Dealer equity options

Dealer securities futures contracts.

Non-equity options, including index options

Specifically, these products are subject to the "60/40 rule," under which 60 percent of the gain (or loss) on a trade is treated as a long-term gain (or loss), regardless of how long the contract is held in a portfolio. The remaining 40 percent is treated as a short-term gain (or loss).

Given the wide discrepancy between short- and long-term capital gains tax rates, the impact of this 60/40 rule can be significant. Long-term capital gains are taxed at just 15 percent, while short-term capital gains are taxed as regular income, subject to marginal rates reaching up to 39.6 percent.

Suppose, for instance, that a successful index option trade netted $10,000. With the 60/40 rule, $6,000 of that profit would be taxed at the 15 percent long-term rate, requiring a payment of $900 in taxes; the remaining $4,000 would be taxed at the marginal tax rate, requiring a payment of up to $1,584. The net tax payment would total up to $2,484.

Can you review the taxation of IRC 1256 contracts?

Form 6781 - 1099-b - 60/40 – mark to market (for any open contracts) – not subject to wash rules. Any regulated futures contract on an exchange.

Tax Rules for Calculating Capital Gains from Trading Options

Calculating capital gains from trading options adds additional complexity when filing your taxes.

A stock option is a securities contract that conveys to its owner the right, but not the obligation, to buy or sell a particular stock at a specified price on or before a given date. This right is granted by the seller of the option in return for the amount paid (premium) by the buyer.

Any gains or losses resulting from trading equity options are treated as capital gains or losses and are reported on IRS Schedule D and Form 8949.

Special rules apply when selling options:

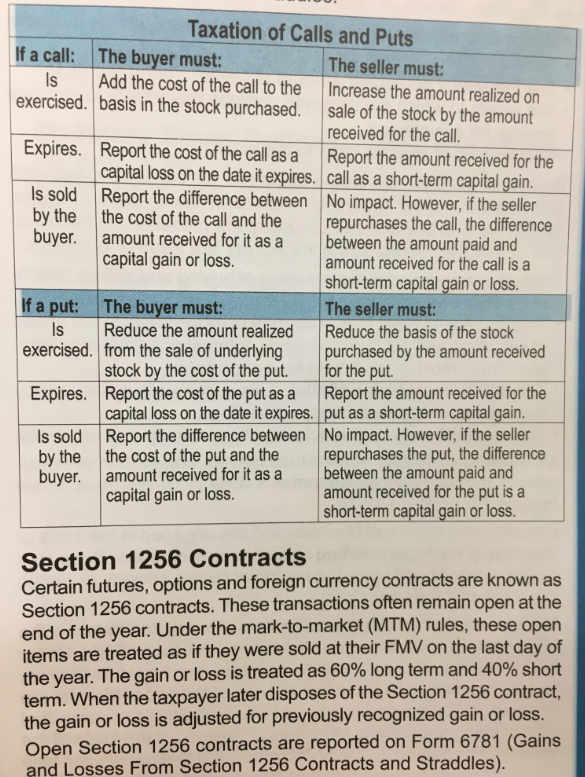

IRS Publication 550 page 60 features a table of what happens when a PUT or CALL option is sold by the holder:

When a Put:If you are the holder:If you are the writer:

Is sold by the holder - Report the difference between the cost of the put and the amount you receive for it as a capital gain or loss.*This does not affect you. (But if you buy back the put, report the difference between the amount you pay and the amount you received for the put as a short-term capital gain or loss.)

When a Call:If you are the holder:If you are the writer:

Is sold by the holder - Report the difference between the cost of the call and the amount you receive for it as a capital gain or loss.*This does not affect you. (But if you buy back the call, report the difference between the amount you pay and the amount you received for the call as a short-term capital gain or loss.)

Notes:

If you are the holder of a put or call option (you bought the option) and you sell it before it expires, your gain or loss is reported as a short-term or long-term capital gain depending on how long you held the option.

If you held the option for 365 days or less before you sold it, it is a short-term capital gain.

If you held the option for more than 365 days before you sold it, it is a long-term capital gain.

However, if you are the writer of a put or call option (you sold the option) and you buy it back before it expires, your gain or loss is considered short-term no matter how long you held the option.

Option Expiration

All stock options have an expiration date. If an option expires, then this closes the option trade and a gain or loss is calculated by subtracting the price paid (purchase price) for the option from the sales price of the option. It doesn't matter if you bought the option first or sold it first.

If you bought an option and it expires worthless, you naturally have a loss. Likewise, if you sold an option and it expires worthless, you naturally have a gain. If your equity option expires, you generated a capital gain or loss, usually short-term because you held the option for one year or less. But if it was held longer, you have a long-term capital loss.

IRS Publication 550 page 60 features a table of what happens when a PUT or CALL option expires:

When a Put:If you are the holder:If you are the writer:

Expires - Report the cost of the put as a capital loss on the date it expires.*Report the amount you received for the put as a short-term capital gain.

When a Call:If you are the holder:If you are the writer:

Expires - Report the cost of the call as a capital loss on the date it expires.*Report the amount you received for the call as a short-term capital gain

Notes:

If you are the holder of a put or call option (you bought the option) and it expires, your gain or loss is reported as a short-term or long-termcapital gain depending on how long you held the option.

If you held the option for 365 days or less before it expired, it is a short-term capital gain.

If you held the option for more than 365 days before it expired, it is a long-term capital gain.

However, if you are the writer of a put or call option (you sold the option) and it expires, your gain or loss is considered short-term no matter how long you held the option.

Sounds simple enough, but it gets much more complicated if your option gets exercised.

Option Exercises and Stock Assignments

Since all option contracts give the buyer the right to buy or sell a given stock at a set price (the strike price), when an option is exercised, someone exercised their rights and you may be forced to buy the stock (the stock is put to you) at the PUT option strike price, or you may be forced to sell the stock (the stock is called away from you) at the CALL option strike price.

There are special IRS rules for options that get exercised, whether you as the holder of the option (you bought the option) exercised your rights, or someone else as the holder of the option (you sold the option) exercised their rights.

IRS Publication 550 page 60 features a table of what happens when a PUT or CALL option is exercised:

When a Put:If you are the holder:If you are the writer:

Is exercised - Reduce your amount realized from sale of the underlying stock by the cost of the put.Reduce your basis in the stock you buy by the amount you received for the put.

When a Call:If you are the holder:If you are the writer:

Is exercised - Add the cost of the call to your basis in the stock purchased.Increase your amount realized on sale of the stock by the amount you received for the call.

Your option position therefore does NOT get reported on Schedule D Form 8949, but its proceeds are included in the stock position from the assignment.

When importing option exercise transactions from brokerages, there is no automated method to adjust the cost basis of the stock being assigned. Brokers do not provide enough detail to identify which stock transactions should be adjusted and which option transactions should be deleted.

Selling Puts Creates Tax Problems

Put selling, or writing puts, is quite popular in a bull market. The advantage of this strategy is that you get to keep the premium received from selling the put if the market moves in two out of the three possible directions.

If the market goes up, you keep the premium, and if it moves sideways, you keep the premium. Time decay which is inherent in all options is on your side. Quite a nice strategy.

Tax Preparation Problems

Since the focus of our site is trader taxes, and not a commentary on various option trading strategies, we will concentrate our discussion on the potential problems that this particular strategy sometimes creates when attempting to prepare your taxes from trading.

If the market heads down (one of the three possible directions), you may find yourself owning the stock as the option may get exercised and the stock gets put to you at the strike price.

IRS Publication 550 states that if you are the writer of a put option that gets exercised, you need to "Reduce your basis in the stock you buy by the amount you received for the put."

Real World Example

This may sound simple, but as usual when it comes to taxes and the real world, nothing is quite that simple as the following example will show:

With stock ABC trading above $53, Joe decides to sell ten ABC NOV 50 PUT options and collect a nice premium of $4.90 per contract or $4,900.00. With current support at $51.00 and less than 5 weeks till expiration, these options should expire worthless and Joe keeps the premium.

In addition, Joe is profitable all the way down to $45.10 ($50.00 - $4.90). So far so good.

But unexpectedly, the market goes against Joe, and ABC drops below the $50 range. Joe is still profitable but he is now open to the option being exercised and the stock being assigned or put to him at $50.

Here is where the fun starts: If all ten of the option contracts get exercised, then 1,000 shares get put to him at the strike price of $50. His brokerage trade history will show this as a buy of 1,000 shares at $50 each for a total cost of $50,000.

But according to the IRS rules, when preparing his taxes, Joe needs to reduce the cost basis of the 1,000 shares by the amount he received from selling the put.

$50,000 - $4,900.00 = $45,100.00 (Joe's adjusted cost basis for the 1,000 shares)

But like I said, nothing in the real world is easy. What happens if the ten contracts do not all get exercised at the same time?

What if two contracts get exercised on day one, three on day two, four more later on day two, and one on day three resulting in his buying four different lots of ABC stock being purchased at $50 per share? How does the premium received from the puts get divided up among the various stock assignments?

You guessed it, Joe bought 200 shares on day one at $50 for a total of $10,000 but he needs to reduce his cost basis by 20% (2/10) of the $4900 premium received from the puts. So his net cost basis for these 200 shares would amount to $9,120 ($10,000 - $980.00) commissions not included.

The same goes for the three other purchases of 300, 400, and 100 shares each with the remaining option premium divided accordingly.

In addition, the option trade needs to be zeroed out because the amount received from the option sale has been accounted for when reducing the stock cost basis.

Brokerages Offer Little Help

Now you would think all of this required accounting would be taken care of by your stock brokerage. Hardly. Prior to 2014 tax year, most brokers simply report the individual option sale and stock purchase transactions and leave the rest to you. Some brokers attempt to identify the exercised options and the corresponding stock assignments, but leave much to be desired in the way they do so.

http://www.tradelogsoftware.com/resources/filing-taxes/options-tax-rules/

When you trade call options, the sale must be reported to the Internal Revenue Service. Unlike the way they do with stock trades, brokerage firms do not send you a Form 1099 reporting the basis of every option trade. Instead, you must use your brokerage statements to match up each individual option trade. Because most call options expire in less than a year, you report them on Form 8949 and Schedule D as short-term capital gains or losses.

Start with Form 8949, Part I, Short-Term Capital Gains and Losses. Check Box C since you did not receive a Form 1099. On Line 1, Column A, Description of Property, enter the name of the company or its symbol, and after that write "call options" and the number of call options you sold. Skip Column B and move to Column C, Date Acquired. Enter the date you purchased the call option, in month, day and year format. In Column D, Date Sold, enter either the date you sold the call option or the date it expired, using a month, day and year format.

Move to Column E, Sales Price, and enter the sale amount reported on your brokerage statement. If the option expired worthless, write "expired" in the column. Now take the amount you paid for the call option as reported on your brokerage statement and enter that figure in Column F. Skip Column G. Use the same procedure to report each call option that you sold. When finished, add up Columns E and F and enter those totals on Line 2, Columns E and F.

Take the amounts on Form 8949, Line 2, Columns E and F, and transfer them to Schedule D, Line 3, Columns E and F. Skip Column G. Move to Column H, Gain or Loss, and subtract Column E from Column F. Enter the gain or loss in Column G. Finish completing the Schedule D, and transfer the final amount to Form 1040, Line 13.

Items you will need

Monthly brokerage statements

IRS Schedule D

IRS Form 8949

Tip

Keep a ledger of each option trade and compare it with your monthly brokerage statement to keep accurate records of your transactions.

LEAPS, or long-term equity anticipation securities, are options that are normally held one year or longer and are reported as long-term capital gains or losses.

Warning

If you sell a covered call and the call is exercised, the amount you receive becomes part of the stock transactions gain or loss.

The thing about options is there are options, right? You can sell a contract short or buy it long. You can get assigned or you can exercise. With so many choices, what does the tax reporting look like?

Scenario 1: Buy Long, Then Sell

Let’s say you bought an XYZ July 17 2015 @ 92.5 put option contract for $5.30 on September 24, 2014. By the beginning of February, it was continuing to decline and you needed to jump ship, selling it for $1.16. This transaction is simple and straightforward. Your cost is $5.30, plus transaction costs, and your proceeds are $1.16, minus transaction costs, which your 1099-B will reflect. Seems too easy, perhaps? Let’s see what happens if you switch it around and sell it short.

Scenario 2: Sell Short, Then Buy to Cover

Go ahead you traders who can deal with the risk (you know who you are), sell the XYZ contract short at $5.30 then close with a $1.16 purchase. The IRS decided to make this transaction just a wee bit tricky, but don’t worry. We’ll explain. Your 1099 is going to show a proceeds amount of $4.14 (modified by transaction costs) and a basis of $0. Confused? You’re not the only one. The IRS mandates that a trader with a cash-settled, written contract report only the gain or loss as proceeds. Your tax document will not reflect the $5.30 or $1.16 amounts, just your profit of $4.14 less transaction costs. See, that wasn’t too bad. If this was a loss, your proceeds amount would be negative. Just for clarification, GainsKeeper is still going to show the original sale and purchase amounts so that you can understand how your 1099 calculates a profit or loss.

Writing Options

“Writing an option” is trader talk for selling an option contract. While many traders believe that the contract will settle in cash if the position is closed out prior to expiration, the truth is you can be assigned at any time. If the contract is exercised or assigned, it will settle in the underlying security, not cash.

Option expirations are simple to report at tax time. When the contract expires, the premium and transaction costs paid (for option buyers) will be a loss. Option writers will realize a gain equal to the amount of the cash received (the premium less transaction costs) for selling the contract.

Now, Some Choices

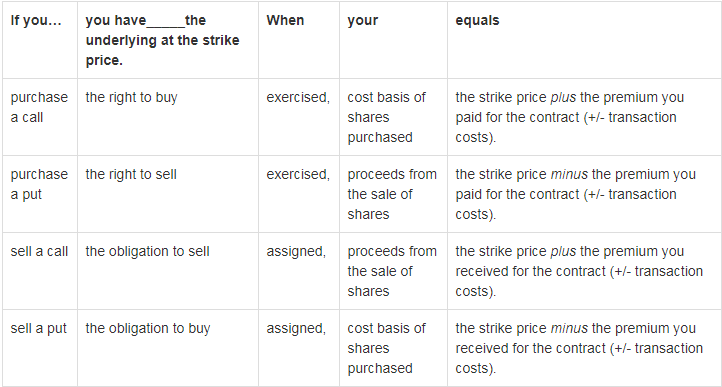

I used to read “Choose Your Own Adventure” books in elementary school. Tax reporting on assignments and exercises is similar. The options are limited (in my chart, not the market!), and there are only four paths you can take when an exercise or assignment takes place. Follow along:

If you… purchase a call

You have the right to buy the underlying at the strike price.

When exercised, your cost basis of shares purchased equals the strike price plus the premium you paid for the contract (+/- transaction costs).

If you… purchase a put

You have the right to sell the underlying at the strike price.

When exercised, your proceeds from the sale of shares equals the strike price minus the premium you paid for the contract (+/- transaction costs).

If you… sell a call

You have the obligation to sell the underlying at the strike price.

When assigned, your proceeds from the sale of shares equals the strike price plus the premium you received for the contract (+/- transaction costs).

If you… sell a put

You have the obligation to buy the underlying at the strike price.

When assigned, your cost basis of shares purchased equals the strike price minus the premium you received for the contract (+/- transaction costs).

Essentially, the contract in and of itself will not be a reportable line item on your 1099 if the contract was exercised/assigned. It’s built into either your cost or proceeds, depending on which path you took.

Want another example? Let’s say you bought an XYZ July 17 2015 @ $100 call for $5, which was exercised. The contract is “done.” However, it isn’t taxable until you sell the shares of XYZ. Whenever you do decide to sell XYZ, your basis is $100 + $5 (strike price plus the premium and plus transaction costs). And keep in mind that could be the next day or 10 years later.