Estate Tax

What is an Estate Tax?

The Estate Tax is a tax on your right to transfer property at your death. It consists of an accounting of everything you own or have certain interests in at the date of death (Refer to Form 706 (PDF)). The fair market value of these items is used, not necessarily what you paid for them or what their values were when you acquired them. The total of all of these items is your "Gross Estate." The includible property may consist of cash and securities, real estate, insurance, trusts, annuities, business interests and other assets.

Once you have accounted for the Gross Estate, certain deductions (and in special circumstances, reductions to value) are allowed in arriving at your "Taxable Estate." These deductions may include mortgages and other debts, estate administration expenses, property that passes to surviving spouses and qualified charities. The value of some operating business interests or farms may be reduced for estates that qualify.

After the net amount is computed, the value of lifetime taxable gifts (beginning with gifts made in 1977) is added to this number and the tax is computed. The tax is then reduced by the available unified credit.

What is the estate tax exclusion amount and is it subject to change?

Unified Credit Against Estate Tax. For an estate of any decedent dying in calendar year 2018, the basic exclusion amount is $11,180,000 for determining the amount of the unified credit against estate tax under § 2010.

https://www.irs.gov/irb/2018-10_IRB#RP-2018-18

What assets are included in a decedent’s gross estate for estate valuation purposes?

Assets Included in Your Gross Estate

The assets that will be included in your gross estate for estate tax purposes are as follows:

Bank Accounts - Including checking, savings, money markets, and CDs. If the account is in your sole name (including payable on death accounts) or in your Revocable Living Trust, the entire value is included; if the account is in joint names with your spouse with rights of survivorship, only 50% of the value is included; if the account is in joint names with someone other than your spouse with rights of survivorship, 100% of the value is included unless it can be proven that the other account owners made contributions to the account; if the account is in joint names as tenants in common, only your proportionate interest is included.

Investment Accounts - Including brokerage accounts and mutual funds. If the account is in your sole name (including payable on death accounts) or in your Revocable Living Trust, the entire value is included; if the account is in joint names with your spouse with rights of survivorship, only 50% of the value is included; if the account is in joint names with someone other than your spouse with rights of survivorship, 100% of the value is included unless it can be proven that the other account owners made contributions to the account; if the property is in joint names as tenants in common, only your proportionate interest is included.

Stocks and Bonds Held in Certificate Form - If the stock or bond is in your sole name or in your Revocable Living Trust, the entire value is included; if the stock or bond is in joint names with your spouse with rights of survivorship, only 50% of the value is included; if the stock or bond is in joint names with someone other than your spouse with rights of survivorship, 100% of the value is included unless it can be proven that the other account owners helped to purchase the stock or bond; if the stock or bond is in joint names as tenants in common, only your proportionate interest is included.

U.S. Savings Bonds - If the bond is in your sole name (including payable on death bonds) or in your Revocable Living Trust, the entire value is included; if the bond is in joint names with your spouse with rights of survivorship, only 50% of the value is included; if the bond is in joint names with someone other than your spouse with rights of survivorship, 100% of the value is included unless it can be proven that the other account owners helped to purchase the bond; if the bond is in joint names as tenants in common, only your proportionate interest is included.

Personal Effects - Including furniture and furnishings; clothing; jewelry; antiques; collectibles; artwork; books; guns; computers; TVs and the like.

Automobiles, Boats, and Airplanes - If the vehicle is in your sole name or in your Revocable Living Trust, the entire value is included; if the vehicle is in joint names with your spouse, only 50% of the value is included; if the vehicle is in joint names with someone other than your spouse, 100% of the value is included unless it can be proven that the other account owners helped to purchase the vehicle.

Monies Owed to You - This includes mortgages held by you, personal loans you've made, and wages, bonuses, commissions and royalties owed to you at the time of your death.

Life Insurance - If you own the policy on your own life, 100% of the proceeds are included; if you own the policy on someone else's life, only the cash value is included.

Retirement Accounts - This category includes Roth and Traditional IRAs; Simple and SEP IRAs; 401(k)s; 403(b)s and annuities; 100% of the value is included.

Closely Held Business Interests - This category includes sole proprietorships, partnerships, limited liability companies and stock held in closely held corporations. The value of your ownership interest is included.

Real Estate - If the property is in your sole name or in your Revocable Living Trust, the entire value is included; if the property is in joint names with your spouse with rights of survivorship, only 50% of the value is included; if the property is in joint names with someone other than your spouse with rights of survivorship, 100% of the value is included unless it can be proven that the other property owners helped to purchase the property; if the property is in joint names as tenants in common, only your proportionate interest is included.

Certain Trust Assets - Certain trusts of which you are a beneficiary, including any trust over which you have a "general power of appointment," will be included in your gross estate at the full value of the trust property. This includes the full value of an "A Trust" established for your benefit as a surviving spouse using true "AB Trust" planning.

Taxable Lifetime Gifts - These are gifts that you made in excess of the annual gift tax exclusion amount in the year in which you made the gift. The exclusion amount used to be $10,000 per gift and is currently $12,000 but will go up to $13,000 in 2009.

Certain Transfers Made Within 3 Years of Death - This includes life insurance owned by you and transferred into an Irrevocable Life Insurance Trust within 3 years of your date of death.

What is the three-year rule?

Section 2035 of the tax code, which stipulates that assets that have been gifted through an ownership transfer, or assets for which the original owner has relinquished power, are to be included in the gross value of the original owner'sestate if the transfer took place within three years of his or her death.

The three-year rule prevents individuals from gifting assets to their descendants or other parties once death is imminent in an attempt to avoid estate taxes. The rule does not include all assets gifted or transferred in that three-year period and is mainly focused on insurance policies or assets in which the deceased retains an interest.

What is income in respect of the decedent (IRD)?

Income in Respect of a Decedent (IRD) refers to untaxed income which a decedent had earned or had a right to receive during his or her lifetime. ... However, the beneficiary may be able to take a tax deduction from estate tax paid on IRD.

Annuities

Tax deferred plans (401k)

Unpaid bonus or wages

First, you have to calculate the estate taxes due on the entire estate, and then you subtract the item of IRD and calculate the estate tax again. The difference between the results is the amount of federal estate tax attributable to the item of IRD. If two or more beneficiaries share the item of IRD, each beneficiary’s percentage of the total tax deduction will be equal to his or her percentage of the item of IRD.

Can an alternate valuation date be used instead of date of death valuation for estate tax?

6 months after death regardless of nine month filing deadline.

• Any property distributed, sold, exchanged, or otherwise disposed of or separated or passed from the gross estate by any method within 6 months after the decedent's death is valued on the date of distribution, sale, exchange, or other disposition. Value this property on the date it ceases to be a part of the gross estate; for example, on the date the title passes as the result of its sale, exchange, or other disposition.

• Any property not distributed, sold, exchanged, or otherwise disposed of within the 6-month period is valued as of 6 months after the date of the decedent's death

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-dft/i706--dft.pdf

Why would the personal representative choose to use the alternative valuation date values instead of the date of death values?

The advantage is that if one or more estate assets have lost a significant amount of value during the six months after death, this will reduce the amount of the estate tax that is due.

If the alternate valuation date values are used, all assets must be revalued, not just those that have gone down in value. This might affect the overall reduction in the value of the estate and result in less tax savings. Each savings of $10,000 in value might be offset by $10,000 gain in value of another item of property.

Using the alternative valuation date can also affect the step-up in basis enjoyed by beneficiaries who later sell inherited assets. The stepped-up tax basis in an inherited asset is the asset's value as of the date of valuation for estate tax purposes.

http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-utl/21_-_inherited_assets_-_stepped-up_basis.pdf

How do I elect the alternate valuation date?

The personal representative must elect to use of the alternate valuation date within one year of the due date of the federal estate tax return, IRS Form 706, including extensions.

There is no way to request an extension for making the election. The election is irrevocable after it is made.

The personal representative makes the election by indicating so on IRS Form 706 at line 1, page 2, part 3.

How are marketable securities valued for estate tax purposes?

Bequests of Stocks & Bonds

When a security is included in the gross estate of a decedent, Treasury Reg. §20.2031-2(b)(1) contains language almost identical to the gift tax regulations: “the mean between the highest and lowest quoted selling prices on the date of the gift is the fair market value per share or bond.”

What is the basis and holding period for inherited property?

The holding period begins on the date of the decedent's death. Inherited property is considered long term property. If you sell or dispose of inherited property that is a capital asset, you have a long-term gain or loss from property, regardless of how long you held the property.

Most taxpayers are familiar with the step-up basis rules for inherited assets [IRC §1014]. Fewer taxpayers are familiar with the holding period rules.

Assets acquired from a decedent (to which IRC §1014 applies) automatically receive long-term holding period treatment when sold (either by the decedent’s estate or a beneficiary). [IRC §1223(9)]

From IRS Publication 544 Sales and Other Dispositions of Asset:

Inherited property. If you inherit property, you are considered to have held the property longer than 1 year, regardless of how long you actually held it.

From IRS Publication 559 Survivors, Executors, and Administrators:

Holding period. If you sell or dispose of inherited property that is a capital asset, you have a long-term gain or loss from property held for more than 1 year, regardless of how long you held the property.

What is the due date for the estate tax return?

9 months after death.

https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/26/20.6075-1

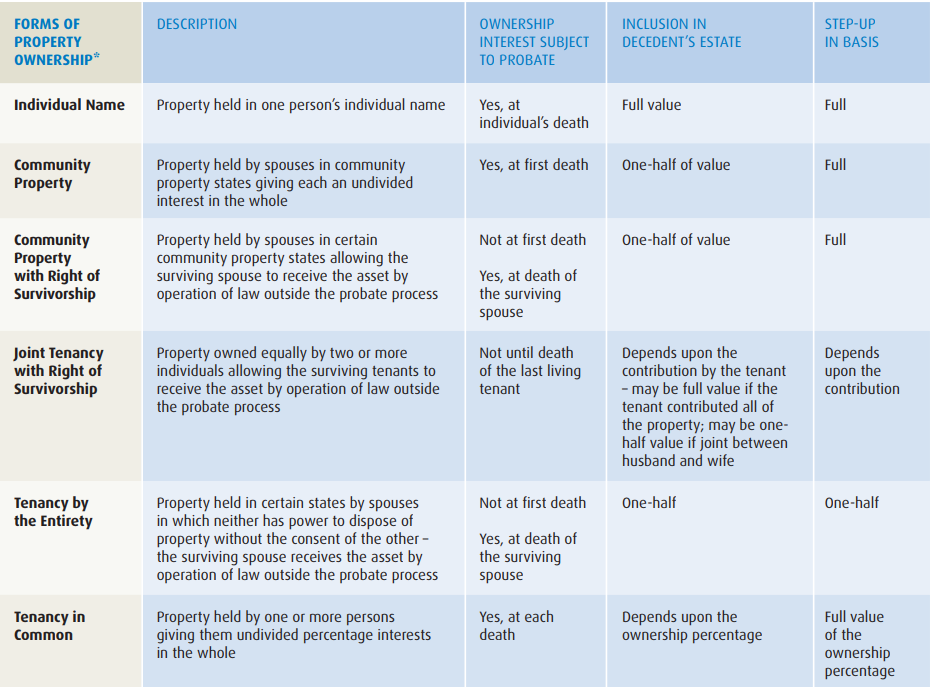

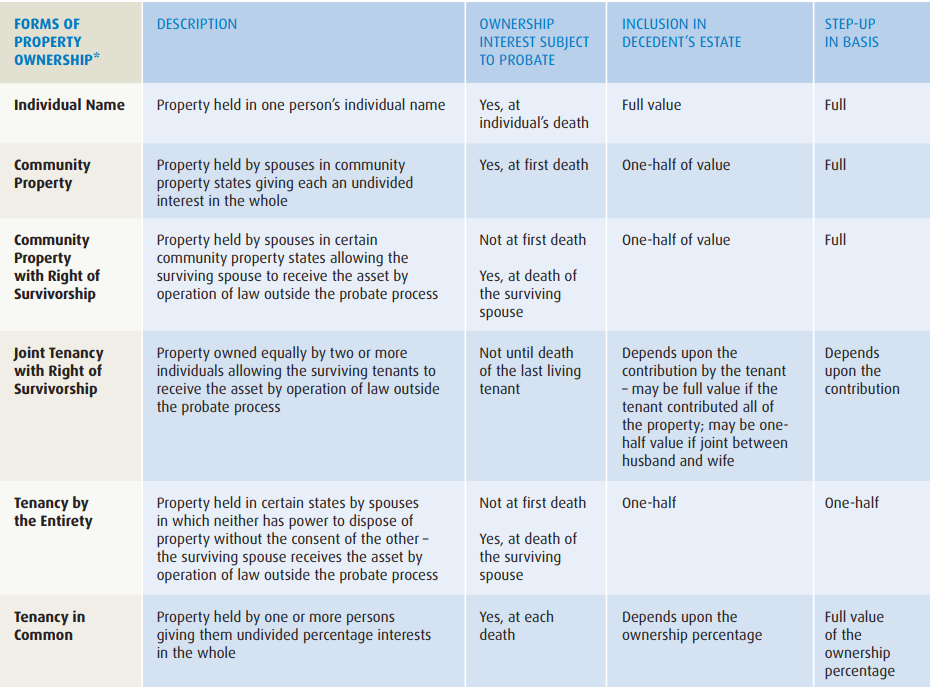

What are the various asset-titling options and the estate tax result of each?

What are the community property states?

The states having community property are Louisiana,Arizona, California, Texas, Washington, Idaho,Nevada, New Mexico, and Wisconsin. Community property states follow the rule that all assets acquired during the marriage are considered "community property".

http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p555.pdf - Page 9

http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-pdf/p551.pdf

Death on the weekend. Form 706 Instructions - page 23

Should You Leave Roth IRA Balances to Charity?

Naming a charity as the beneficiary of your Roth IRA is generally inadvisable. Instead, leave Roth balances to your loved ones by designating them as the account beneficiaries. Here’s why: As long as your Roth IRA has been open for more than five years before withdrawals are taken by heirs, all their withdrawals will be federal income tax-free.

But if you leave Roth IRA money to charity, this valuable tax break is completely wasted.

Remember: the required five-year period before federal-income-tax-free withdrawals can be taken starts on Jan. 1 of the year for which you made the initial contribution to your Roth IRA. This includes contributions made by converting traditional IRA balances to Roth status.

For example, let’s say you make your initial Roth IRA contribution for the 2015 tax year on April 14 of 2016. You nevertheless start counting on Jan. 1, 2015 for purposes of meeting the five-year rule.

This strategy makes sense, because an IRA that is owned by a relatively well-off person can be a sub-optimal asset to leave to your loved ones. Under current tax law, such an IRA may be subject to double or even triple taxation.

Take a look at how it works:

– First, your traditional IRA account is included in your estate for federal estate tax purposes when you die. That’s tax number one.

– Next the taxable portion of the IRA balance (which is often the entire amount) is counted again as “income in respect of a decedent” (IRD) for federal income tax purposes. That means federal income tax will be owed when IRA withdrawals are taken by your estate or your heirs. That’s tax number two.

– To make matters even worse, state income tax may be due as well. If so, that’s tax number three.

After all these taxes have been paid, your heirs may receive only a very small fraction of your IRA money while tax collectors get the lion’s share.

A Charity as IRA Beneficiary is the Cure

A tax-smart solution is to leave some or all of your IRA money to charitable beneficiaries while leaving everything else to other heirs you choose. The net result will be more after-tax cash for them. At the same time, you can satisfy charitable inclinations after you die. Sound good? Here are the details.

By naming one or more tax-exempt charitable organizations as beneficiaries of your IRA, you leave that money to the charities after your death. Under our current federal tax system, that is the only way to leave IRA balances directly to charity, although proposals have been made to change that.

As an alternative to leaving money to charities after your death, you could take money out of your IRAs now, pay the resulting income tax, and then give cash to qualified organizations. Your contributions would be fully deductible for income tax purposes, although income-based restrictions might limit your charitable write-offs. In that case, you may have to claim your deductions over several years. Depending on your taxable income, you may never be able to completely write off large donations. As you can see, this can be an inefficient way to satisfy your charitable desires.

On the other hand, leaving IRA money directly to charities upon your death by designating them as account beneficiaries is very tax-efficient. First, an IRA balance left to charity avoids the federal estate tax, since it is removed from your estate for federal estate tax purposes. Second, there’s no federal income tax due on the IRA money (the IRD rules don’t apply). There’s no state income tax either. Finally, no income taxes are due when your favorite tax-exempt charities take their withdrawals from the IRAs. So you avoid double or triple taxation in a simple way.

If you are planning to make bequests to your loved ones, you can leave gifts of assets that are eligible for the federal income tax basis “step-up” to fair market value, as of the date of your death. These include common stocks and mutual fund shares held in taxable investment accounts, ownership interests in your small business, real estate and just about anything else that qualifies for capital gain treatment when it is sold. Thanks to the basis step-up break, these assets can be sold by your heirs with little or no income tax (only post-death appreciation would be taxed). So there are no double taxation worries. However, they will be included in your estate for federal estate tax purposes, assuming your estate is taxable.

When all is said and done, this strategy allows you to leave more to your favorite charities, more to your loved ones and less to the tax collector.

You can generally take the same steps with other types of tax-deferred retirement plan accounts as long as the accounts have specific balances. These include 401(k), corporate profit-sharing, SEP and Keogh retirement accounts. If you’re married, however, state law may require you to obtain your spouse’s permission to name charities as beneficiaries of these accounts.

Conclusion: Designating your favorite charity as a beneficiary of your traditional IRA (and other tax-deferred retirement accounts, if your spouse approves) can be a tax-smart maneuver. With advance planning and the federal estate tax exemption, you have much more opportunity to minimize both federal and applicable state income and estate taxes. Contact your tax adviser if you have questions or want additional information.

https://www.wsrp.com/leaving-ira-money-charity-tax-smart-strategy/

Who pays taxes on an estate?

There are two kinds of taxes owed by an estate: One on the transfer of assets from the decedent to their beneficiaries and heirs (the estate tax), and another on income generated by assets of the decedent’s estate (the income tax). This page contains basic information to help you understand when an estate is required to file an income tax return.

When someone dies, their assets become property of their estate. Any income those assets generate is also part of the estate and may trigger the requirement to file an estate income tax return. Examples of assets that would generate income to the decedent’s estate include savings accounts, CDs, stocks, bonds, mutual funds and rental property. IRS Form 1041, U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts, is required if the estate generates more than $600 in annual gross income.

The decedent and their estate are separate taxable entities. Before filing Form 1041, you will need to obtain a tax ID number for the estate. An estate’s tax ID number is called an “employer identification number,” or EIN, and comes in the format 12-345678X. You can apply online for this number. You can also apply by FAX or mail; see How to Apply for an EIN.

A decedent's estate figures its gross income in much the same manner as an individual. Most deductions and credits allowed to individuals are also allowed to estates and trusts. However, there is one major distinction. A trust or decedent's estate is allowed an income distribution deduction for distributions to beneficiaries. Income distributions are reported to beneficiaries and the IRS on Schedules K-1 (Form 1041).

For calendar year estates and trusts, file Form 1041 and Schedule(s) K-1 on or before April 15 of the following year. For fiscal year estates and trusts, file Form 1041 by the 15th day of the 4th month following the close of the tax year. If more time is needed to file the estate return, apply for an automatic 5 month extension of time to file using IRS Form 7004, Application for Automatic Extension of Time to File Certain Business Income Tax, Information, and Other Returns.

In general, an estate must pay quarterly estimated income tax in the same manner as individuals. For more information on when estimated tax payments are required see the Form 1041 instructions. For more information on how to make estimated tax payments for an estate see IRS Form 1041-ES, Estimated Income Tax for Estates and Trusts.

Estate tax on the transfer of assets from the decedent to beneficiaries and heirs is reported on IRS Form 706, United States Estate (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return.